Somewhere in Mobtown’s third or fourth year, the inevitable happened and it fell to me not just to clean the bathrooms (which I had often done) but to empty out the small trash cans into which the scourings of menstruation are deposited. I had cannily avoided this for years, hoping to maintain my feminist credentials while exposing myself to these biological remnants as little as possible, at least once they had been discarded and congealed. Like all noble pursuits, this battle was a rearguard action, a desperate bid for time. Glorious. Doomed.

My back against the wall, I resolved to undertake the task in the finest tradition of male stoicism. The cans had been unattended for a few days too long, and I felt bad about this, as I had often had occasion to lament the state of the bathrooms after a well-attended event, wondering how it was that people had the time or interest during a night out to make confetti of so much toilet paper and let it snow down gently across the tile. Perhaps they were angry about the full cans, I reasoned generously. Buoyed by these benevolent considerations and having dispatched the first can with fortitude, I placed a cautious toe on the pedal that would activate the lid of the second, paused for a beat, and pressed. Leaping back, I yelped, and the can’s lid snapped shut on what appeared to be a mid-sized gray mammal, alive or dead I could not say.

I retired to my safe space behind the bar and fortified myself with a dram of whiskey before facing the problem in the steady and objective manner that is the adornment of small businesspeople everywhere. If, as seemed most likely, the animal was dead, I had to dispose of it, and a handy pair of tongs would likely do the trick. If, on the other hand, the animal was merely dazed or wounded, prudence dictated that I use the plastic slop bucket and colander from behind the bar to outflank and trap the intruder before releasing it into the wilds of Pigtown.

So it was that–armed with bucket, colander, and tongs–I made my way across the expanse of hardwood towards the bathrooms. A second dram of whiskey steeled my purpose and warded off incipient puritanism. I struggled to put certain haunting questions out of my mind. Was this animal a pet? Was its placement here in the ballroom in my own menstrual cans a misguided attempt to responsibly dispose of roadkill? Had the animal somehow stepped on the pedal and activated the lid, opening its own tomb? Worse yet, had it been used for some wildly inappropriate, grisly menstrual purpose and then, strange to say it, been appropriately discarded? These were the questions as I approached the relevant can, caught between pity and horror. I toed the can again, ready to swoop with bucket and colander should the mammal show twitches of life. But there were none. I jostled the can gently. Still nothing. Switching to the menstrual tongs, and whispering a prayer to whatever wretched god presides over such things, I laid hold of the furry mass, clamped it firmly, and pulled from the sepulcher of the can a coon skin cap, tail and all.

***

How this Davy Crockett cap came to be in the Ballroom and how it came to be disposed of in this strange manner is one of the establishment’s abiding mysteries, which are legion. This kind of thing is characteristic of the service industry as a whole and of every off-kilter, screwy job I have ever worked. You can eyeball human behavior pretty well in such places, and it is genially and hilariously discussed by the workers who do the eyeballing, as anyone who has waited tables or worked in a kitchen can attest. Over the years incidents accrue and a place becomes a spot with an internal culture that is distinct from, though intertwined with, the experience of the people who go there. The service side of the bar is a world unto itself, as is managing the show. These roles give you a flipped view of your community, like looking at a photo negative, particularly when they happen at night. There are many drawbacks to that life, but it’s hard not to romanticize it. Turning the lights off in a place that was filled with life and activity a mere hour ago is a melancholy, lovely feeling. I’ve never gotten over that.

I have been lucky enough to work in such places for my entire adult life, places where you can share a drink or a cigarette after hours and decompress or run out the door to make last call at Club Charles or CVP, only to trade stories and talk shit with people who have left their own service gigs for the same purpose. You drink in a weird kind of life when you work at the places people go to unwind, and if you work at such things long enough you become unsuited to the office world of best practices, metrics, meetings, and memos. For me, that is a happy thought, and—despite the unspeakable volumes of horseshit we’ve dealt with in the past decade—I have loved running this place. I have felt like a human here.

What follows is a baggy assortment of thoughts and stories about my experience at the Ballroom. I don’t anticipate that they will be of any real use, but they have become precious to me over the years, and I collect them and turn them over in my mind and chuckle at them or groan. Small treasures. Perhaps they may be of some interest to the many strange people who have, in their wanderings, taken some time to haunt this place.

***

Early on, before we had a bar, one of the staff behind the counter waved me into the vestibule where people pay, and I boldly entered, ready for trouble. A man was leaning against the ticket window demanding entry and languorously eating a thick mayonnaise sandwich. The condiment had squeezed out between the slices of bread and caked his hands, arms, and shirt. Opting for honesty, I told the fellow that he appeared very high indeed and could not come back until he was sober. I asked him if he would go outside to talk with me (an old trick), and he consented. As I walked him out the door and across the alley, thinking myself very clever, he turned with surprising deftness, punched me in the face, and pushed me in front of a car turning down that same alley.

The cops were, as chance would have it, idling across the street. They cuffed the man and seated him in that dejected position on the sidewalk that they love so much, and then asked me if I’d like to press charges. I said no, but asked in turn whether they could take him somewhere to get help, or, barring that, whether they could drive him somewhere far off and drop him there to give me time to close before he could return and resume hostilities. They informed me that the first option was up to him (he declined) and that the second violated his constitutional rights (which was fair enough). So the man was uncuffed, and he disappeared down the street. The cops left.

This not being my first rodeo, I went back inside to grab our crowbar. As I remerged from the Ballroom’s solid red doors, my worthy assailant was already making his way back across the street. I held the crowbar above my head with both hands like John Cusack in Say Anything and gave it a few tight shakes. The pugilist stopped and stared. A long intimate moment passed before he turned and made his way into the night. I walked back into the Ballroom, wondering whether we should make a policy for this kind of thing. An attorney friend informed me that I was probably within my rights to hold a crowbar but should avoid “brandishing it.” If any other wisdom was gleaned from the experience, I have forgotten it.

***

Any number of felonious/hilarious misdeeds have been perpetrated near or against me since this place kicked off. Once, sitting outside the ballroom and looking at my phone, I was shocked to find it raptured out of my hands by a nimble bicyclist who was down the street and well out of reach before I had the chance to object, much less make the reasoned argument that I could have just given him cash, saving me a hassle and increasing his profit. This was some years before another bicyclist, on the exact same patch of sidewalk, punched me in the face as I stepped aside to let him pass. There has been more punching (of me) in this job than I had anticipated.

Not long before the pandemic, a customer approached to say that her bicycle—which had been locked to the green rack just outside the door—had disappeared. I accompanied her outside to investigate, and found that not only was the bicycle gone, but the lock had gone missing as well. There was no evidence that a bicycle had ever occupied the lonely spot. I stood there scratching my head, then leaned against the rack to adopt a jaunty conversational pose. The bike rack fell clattering to the ground, and I nearly took a spill myself. The enterprising thief had removed the bolts holding it to the ground, and then carefully replaced the rack itself. This is as good an illustration of the difference between a workman and an artist as I can conjure, and I often think back on the incident with admiration.

By way of digression, I have to say that bicycles have been one of the great annoyances of my professional life. Something in the makeup of the bicyclist includes the confidence to ask if they can bring the damn things into the Ballroom, and, of course, any answer in the negative elicits the most pitying and self-righteous of environmental gazes. I often fantasize about buying a bicycle, covering it in grime, and bringing it to the living rooms of these people, where it can tip over, smash things, block fire exits, and raise their blood pressure.

Before I leave the subject forever, I have to say that a scampy young regular of ours has fired off a new salvo in the bicycle wars. He has taken to showing up at the ballroom on an electric unicycle (what abominations will I not live to behold?), and I have struggled to make my objections to this contraption rational, since, being no bigger than a backpack, it is stowable beneath a pew. Still, I object to the wearing of backpacks as much as to anything else, and the goddamn thing looks, when not in use, exactly like a giant Roomba. Explaining why something like this raises my hackles (and should raise yours) is an exercise in tautology. I do not know when style and grace will return to the world, but, when they do, people will not be sailing down the street on Roombas, I can tell you that much.

In other felonious happenings, our safe has been stolen twice, despite alarm systems and every reasonable precaution. There’s never enough money in it to make the Spiderman-style hijinks required for these thefts remotely worthwhile, which makes me question what percentage of criminals actually operate at a loss (and whether, on the way home from unremunerative heists, they console themselves with platitudes—better luck next time, at least we did our best). During the first such theft, a duo of thieves departed the building with a large gun safe that we’d gotten on discount at Cosco. They dropped the thing repeatedly on their way out, and the sidewalk still bears the scars. We thought that would be the last we’d ever hear about it, but about a week later, the police told us that it had been dumped on a boat launch in the harbor. I made the trip down and found it there, half submerged, with a perfectly circular hole cut in the top of it. The waves lapped at its sides, and warranty documents drifted slowly out into the Chesapeake.

***

The internal operations of a skeleton crew organization like this are as chaotic and whimsical as anything that comes in off the street. Sarah Sullivan, for example, has a habit of playing pranks on me, must of them calculated to feast on my deepest insecurities. Under normal circumstances, this would be cruel, but I suspect that the way I present and carry myself makes it a necessary corrective. One notable day, as I was driving towards the ballroom with our old monstrous business partner (of whom I have spoken at length elsewhere), I answered the phone, and a woman with a British accent told me that Sarah had listed me as a reference, and that she was very excited about hiring her. My heart sank at the thought of running the place with the monstrous partner, but I know when to rise to the occasion, so I collected myself and gave a stunning reference. Sarah, I said, was someone we would fight to keep and someone to whom they would, if they had any sense, make a very generous offer. She was a powerhouse, a self-starter. She identified problems before they were problems. That kind of nonsense. Having arrived, I entered the ballroom to find Sarah grinning at me–and her mother, Cindy (who had, for some reason, improvised a British accent), cackling on speakerphone. My goat had been gotten and Sarah had extracted some compliments in the bargain.

Once one of her pranks backfired, or, at the least, left me smelling like roses. At a New Year’s Eve event in North Carolina, Sarah had spent days crafting a particularly devious act of wickedness. She intended, she told me over drinks at the bar, to propose to Charlie at midnight on the 31st. She was finally ready; she’d made her decision and was eager to move forward with the next stage of her life, etc. Naturally, I rejoiced at the news that my two beloved friends intended to take this step together, and I pledged my support and silence on behalf of the worthy project. On the fateful evening, a half hour before midnight, Charlie took me aside and asked me for a word in private. I escorted him outside the hotel ballroom and around the corner. Our breath rose in the late December cold.

“Michael,” he said, “I think Sarah is going to propose to me tonight.”

“That’s wonderful, Charlie. Why do you look like someone stepped on your tail?”

“I love her, but I’m just not ready.” He looked pained in a way I had never seen, and I could feel the earth moving under my feet. I did not want to see this relationship fail. I resolved to say as much.

“Charlie, I’m sure that Sarah can wait if that’s what you want, but my formal advice is that you have a good situation on your hands. She’s great; you’re great. Both of you have too many foibles to be good for many other people. This shit works and makes a kind of weird sense. If you don’t want to be with anyone right now, then cold feet would make sense, but, otherwise, I think you’d be an idiot to hold out for something better. It’s not coming along.” Charlie looked at me for a long moment, thanked me, and we hugged. He went back in ahead of me.

I took a couple minutes in the cold to reflect, and made my way into ballroom. Sarah was already running towards me, bellowing, “IT WAS A JOKE. WE WERE SETTING YOU UP.” Charlie, it turns out, had returned to the ballroom and suggested making their mock engagement real, lest my heartfelt speech go to waste, and Sarah was having none of it. Both of them looked harried and confused when they had meant to harry and confuse me. It was wonderful, and I have long treasured this memory of my friends’ discomfiture, thinking back on it when I am feeling low. Recordkeeping of this kind is crucial to the maintenance of long-term friendships.

***

Sarah and I have spent a more than a decade of our lives torturing her husband. Before the ballroom opened, we made him carry the sound equipment to venues we rented, a duty he performed for love. I have used him in some rather mischievous alcohol experiments, snuck up on him when he was alone singing in the ballroom, stolen his phone, and sat on his shoulders and insisted that he run laps around the ballroom to Chumbawamba’s Tubthumping (a form of dance training the efficacy of which Charlie’s abilities bear out). Years ago, Sarah and I were talking business on a group text that included Charlie. I was in the office, and Charlie was in the Ballroom teaching. I could hear the first message I sent bing loudly in the main room, as Charlie was using his phone to play music for class. I said as much to Sarah, and we both began texting “bing” to one another, as quick as we could type. I opened the door to the ballroom. A chorus of bings was pouring from the sound system. The students were laughing, and Charlie was pacing back and forth, waving his hands in confusion. His eyes landed on me.

“Goddamit, Michael,” he said.

I can run with Charlie stories. He once loudly and insistently referred to his “hymen” at a bachelor party. A hush fell over the room, and, in a moment of rare and absolute male psychic connection, the other attendees and I looked at him innocently, as if we hadn’t heard. “My hymen!” Charlie said, “my hymen!” We held it together long enough for the tragedy to dawn on him, and, when recognition flooded his face, the room erupted with laughter. Charlie’s hymen has been a watchword ever since.

These stories make me very happy indeed, even as retelling them reminds me that the world has changed and the era of people expressing affection with torture has come to a sad end. Charlie, to whom these things do not come naturally, has bravely and cheerfully undergone all manner of indignities from Sarah and me. He has done every job at the ballroom, even the ones he most despises. When I left the monstrous old partner and slept in the ballroom, Charlie, drunk as can be, abandoned his birthday date with Sarah, and rushed to my aid in a cab. Our conversation was understandably less than useful, but he was there, and it took the edge off. These are things you remember.

I’ll say one more thing about Charlie. Way back before the ballroom, Sarah and I were running an event in a former gym turned African dance theater, which we rented on Fridays. The place was not well-marked, so we sent Charlie outside in a sparkly sequined jacket that I’d stolen or inherited from somebody’s grandmother. He had a large sign to guide people into the parking lot, and his task was simply to stand there and let the sign do its work. I came out to inspect him an hour or so into the event. He was standing manfully at his post, talking to everyone who pulled in, welcoming them with sincere interest. That has been his way for more than ten years: He takes care of people. Conversations that I would end with terrible, rude swiftness, Charlie abides, seems almost to enjoy. Sarah once asked him how he pulls this off, and he replied: “When it starts to get annoying, I just ask them to dance.”

***

And, God help me, it does get annoying. A public venue is bound to bring in some originals, but no amount of experience makes the insanity of the public less baffling.

“Hi,” someone recently said to me, “were you aware that there is no parking tonight?”

“No,” I said, feeling puckish, “where did you put your car?”

“I parked it.”

“Oh.”

“What I mean is that there is very little parking.”

“I’m sorry.”

“You should look into it.”

“You are drastically overestimating my powers.”

Or, one of my favorites:

“Are you going to ask the band to play some blues music tonight?”

“Buddy,” I replied, leaning across the bar, “this is blues music.”

“No, it’s not.”

“It’s a blues band. It’s in the name, ‘The ______ Blues Band.’”

“No, this is Lindy Hop music. It’s fast.”

“Lindy Hop is not a kind of music. And blues is a form not a tempo. Seriously, I know what I’m talking about. I promise.”

“You’re the bartender.”

“This is my venue. I hired the band.“

“I’d like to talk to someone who knows what’s going on.”

“Wouldn’t we all. Let me introduce you to Sarah.”

Anyone in the service industry can tell you that people out for an evening of entertainment—otherwise decent, lovely people—lose all sense of boundaries around service folks at work. A particularly goofy regular of ours who has a habit of taking up more than a reasonable share of my time directed his steps towards me a month or two before the pandemic began. I’m wise to this, and adopt what some of the youngsters here refer to as my “there’s a fire somewhere” walk, a purposeful, no-nonsense gait I assume when I do not wish to be stopped, buttonholed, or otherwise hectored. In this instance, my would-be pesterer was undeterred, and I took the drastic step of fleeing to the bathroom, assuming a private and sacred position at the urinal. This terrorist of the mind followed me in, and I could sense him behind me, waiting for me to finish. Boldly, I resolved never, ever to stop urinating. I underestimated the tenuousness of this man’s connection to decorum. He piped up:

“I didn’t get a receipt at the door.” Is this happening? I thought. It was.

“You want a receipt for a cover charge?” I asked, craning my neck to address him.

“Yes. It is for my financial records.”

“Quite right. Situated as I am—here, at the urinal—what is it you would like me to do about it?”

“You have a POS system. You should really give people receipts.”

“What can I do to end this conversation immediately?” I queried firmly. Charlie, by chance present in the bathroom, guffawed.

“You can give me a receipt.”

I was in too deep. “Fair enough,” I said, “please retire to the bar while I finish my ablutions, and I will be with you shortly.”

This odd fellow left the bathroom, and Charlie grinned at me wickedly (feeling no shame, I might add, for having failed to aid a ballroom operator in distress). I shot him a dark look, and went to the bar where—standing next to highly-competent staff that could have printed a receipt—I printed a receipt.

“Thank you,” the mental terrorist said. “You should really give people receipts.”

“Jesus fucking Christ.”

Speaking of urine—we once hosted an extremely over-the-top fundraiser for a beloved local musical organization renowned for doing extremely over-the-top things. I knew that it was the kind of event where shenanigans would be the order of the day, and I thought our team well-prepared. The group hung an enormous car-sized papier mache skull from one of the circus points; they lit and festooned the ballroom in a stunning manner, and commenced to throw one hell of a party. Midway through one of the band breaks, I stepped outside for a little chill air, and, behold, some hipster attendee was across the street, pissing against a neighbor’s house. This kind of thing, aside from being wrong, is not great for business or our relationship with the community. I ran across the street to upbraid the young idiot and was intercepted by an elderly black pillar of the neighborhood on the same errand. This man had given us the benefit of the doubt when we, a handful of white children, came to the neighborhood to open a venue. He had supported our rezoning when we needed it, and he had backed us when we needed the community organization’s approval for the transfer of our liquor license. In short, he had gone some considerable distance on our behalf, and what we were presenting to him in return was far from what he, and the neighborhood, deserved: a white man producing his dick in public, pissing on black housing.

“I cannot believe what I am seeing, Michael,” the pillar of the community said.

This cut me to the heart. I apologized sincerely and deeply as the hipster weasel looked on, smirking. While our august neighbor stood there, I went back inside, waded through the crowd, and got a bucket of soapy water and a scrub brush. I returned and cleaned the hipster’s urine from the housefront while he continued to look on stupidly. One of the organizers of the event got wind that something untoward was happening, and she caught both me and the douchebag walking back towards the Ballroom.

“Fuck that guy, right?” said the hipster shit.

“On the contrary, fuck you,” I replied.

“What happened?” asked the organizer.

“This little shit is not coming back inside. That’s what happened.” The organizer hemmed and hawed for a moment, understandably confused by my mystic utterance. I took up a stern and forbidding stance in front of the door. The douchebag stood about a foot in front of me.

“I’m coming in,” quoth the skullduggerous shithead.

“If you manage to come in here, you will never be coming back out.”

The hipster shit stared at me menacingly. I stared back, inwardly complimenting myself on saying something awesome. After a few deeply stupid, masculine moments passed, he turned and walked down the block. The organizer informed me that he was in the band and that all of his equipment was inside. I helpfully replied that anyone unfortunate enough to be associated with this trouser snake was welcome to collect his equipment for him and deposit it on the sidewalk. By this point I had partially let down my guard, and I stepped aside to let a customer approach the doors. I noticed that he was wearing a coat buttoned unseasonably high and one of those winter hats with the ear flaps pulled down. I leapt forward in the nick of time, for it was the douchebag returning in disguise.

This is the second story I have involving a furry hat.

***

The hostilities above have crossed my mind often, because the turn toward the comic in otherwise heavy, serious interactions has been repeated time after time at the Ballroom. The douchebag in question represents a large portion of what I hate in the world, but how can I help but laugh at the audacity required for him to return incognito? Many of the villains we’ve encountered have had their comic edges, even those who hurt us most deeply, and something in me balks at the thought of denying or overlooking that. Like my fellow lefties, I will engage in the odd bit of internet moralizing, and I foam at the mouth with the best of them; but, God help me, if I ever do my foaming without a twinkle in my eye, or if I ever fail to preserve some shard of love for the disguised pissers of the world, I hope my loved ones will have the good sense to cudgel me to death.

***

Conflict has shaped the Ballroom and shaped our experience in this city in a way I never anticipated. In the early days we were overly-cautious in dealing with what we now understand to be garden variety malefactors. We have kicked many men out of the ballroom, and a healthy handful of women–at first after long discussion and consultation and eventually with the easy confidence born of experience. These days they are easily sniffed out, and we have a better sense of how transgressing small boundaries invariably leads to transgressing large ones. A warning is given, then ignored. Then we kick people out. The wicked set begin by negotiating and wheedling, but they are too addled by the conviction of their own charm and “rights” for this to last long. Confronted by our absolute unwillingness to hear them out, disbelief gives way to rage. They threaten and wheedle by turns, trying on different approaches, and growing more distraught. The type to need the last word, they tend to leave on a threat, usually some foggy promise that we will be “hearing from” their attorney. I suspect that there are not enough attorneys in the world to represent all the male software engineers who have appealed to them in a rage.

The course of these interactions is depressingly predictable, and we’ve found that the only appropriate approach to douchebags is all-out obstinate resistance. It kills this sort to be stood up to, and they show their true colors pretty quickly. There is good fun to be had in needling them if you have the stomach for that kind of thing. I used to delight in it. Over time, however, I’ve grown to feel that justly resisting people who would compel you to do something or who would use you for their own self-aggrandizing, abusive purposes is still itself a kind of force, and using force gnaws at your soul. Both Sarah and I have grown weary of this stuff (though we are as obstinate as ever), which I take to be a sign of health. We don’t like hurting people.

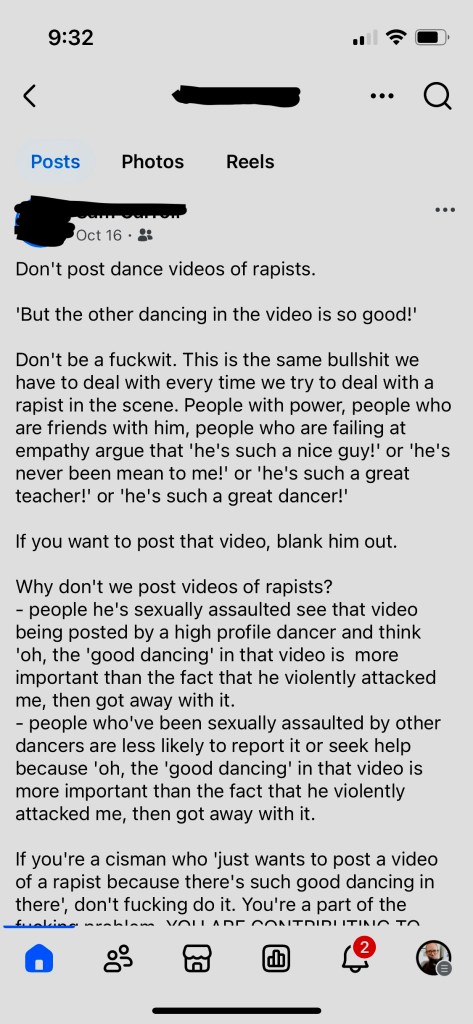

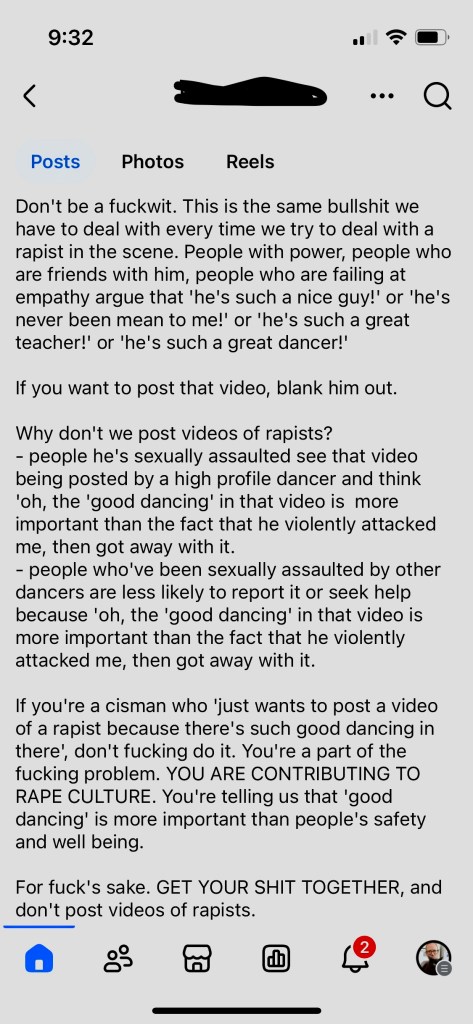

Sometimes things have gotten dicey. I wish more people—particularly people whose primary experience of conflict is displays of nobility on the internet—understood the true cost of dealing with douchebags in a professional capacity and the sometimes physical courage required. When we successfully handle a situation, the injured patron moves on, but we tend to hear from bad actors for a long while after. We still get the odd threatening message or phone call, the occasional suggestion that people are watching. I have one who has been calling me for years and another who constantly tries to harass me through third parties. Sometimes I run into these goons on the street. I occasionally wonder when someone we take to be a manipulative weasel will turn out to be violent (I leave out the occasional street punch). The national community has failed pretty spectacularly in these conversations, more or less declaring that organizers should deal with these things and papering over real concerns with a marrow-deep belief that the correct policies will render the world safe.

I have never quite been able to pin down my discomfort with the urge to offload all responsibility onto organizers and venue operators—with the paradoxical liberal wish for authority figures in general (why, oh why, would we wish to mimic this vilest aspect of conservatism?). Part of it has to do with the unavoidable fact that the desired qualifications would preclude anyone with mental illness or a history of trauma or anything but an inhuman lack of foibles from doing any organizing at all. Sarah has often observed that she is encouraged to be a nuanced, complicated woman right up until something sticky happens. Then woe unto her if she fails to perform as a steely-eyed enforcer of policy on behalf of a shifting liberal consensus, newly minted on Twitter that day. Hesitation, doubt, or even thought is taken as insufficient commitment to orthodox. People who stand by in their own workplaces for reasons of practicality or fear, expect unstinting, heroic action from her.

I think that all of this may be symptomatic of a dangerous desire to carve out authority figures and parental substitutes wherever one can, and I am convinced it’s a cancer in liberalism. The conflicting claims of justice in a given scenario—we want venues to be affordable, but we also want to make sure the musicians get paid fairly, but we also want the equivalent of a full-scale HR department, etc.—should teach us humility. We live and die taking these problems one at a time and doing our best. Anyone peddling grand solutions or is a fool or a villain. There is no replacement for a community willing to take care of its members and welcome in new ones. Heroes and leaders are a distraction.

I have veered far into preaching, and will add only that the majority of my beef (and I believe this is also true for Sarah) is with the national community. The folks at Mobtown—even when they are batty as all outdoors—have shown real gumption in creating a community that reflects shared values. When issues are passed on to us it is, more often than not, the result of unnecessary deference rather than a desire to avoid responsibility. I am very grateful for that.

***

For the most part, I have tried to deal with conflict like an adult, but in one sphere, and one sphere only, I have given full scope to my hostile disposition and love of confrontation. All cities are filled with scammers and flimflam men, but a city like Baltimore produces a rare caliber of swindler, and these it has been my delight to torture. Baltimore Gas & Electric scams are the worst of the lot, preying on the most vulnerable, and I have done everything I can to make these callers cry. I once told a scammer that I hoped he and everyone he loved ended up “eating rat shit in hell,” and the ballsy bastard persisted in trying to con me. Most of the time, they try to maintain a veneer of professionalism, but occasionally they seem truly hurt.

Some years back, I looked up how to report these goons on the BG&E website, and was impressed to be referred to an FBI line. A friendly agent said that I should try and play along to mine for information, and, as this seemed a pleasant sort of change from my usual verbal warfare, I made the attempt. The next call proved to be a doozy:

“Hi, this is a courtesy call from Baltimore Gas & Electric. You have unpaid utility bills, and technicians are on their way to disconnect your electricity.”

“Oh, my,” I replied, “I had no idea. Is there any way I can keep this from happening? I can totally pay.”

“Yes, but you have to act quickly. At this stage in the process we cannot accept an online payment.”

“What should I do?”

“You can pay by cashier’s check. We have a box at a nearby 7-11 where you can deposit payment.” Nothing suspicious here.

“I’m sorry—I have no idea where to get a cashier’s check.”

“You can get one at the 7-11.”

“That sounds really complicated. I have cash. Can you tell me where I can meet you, and I’ll pay you in person. I’ll kick in a little extra for your trouble. I just really want to get this taken care of.” I may not be the world’s greatest actor.

“Do you want to suck my dick?” I admit to being taken aback.

“Do you want me to want to suck your dick?” I began to fear an infinite regress.

“You sound gay.”

“I’m beginning to doubt that you’re calling from BG&E.”

***

It is not, of course, all villains and douchebags, even where conflict is involved. One of my proudest moments, and one of the stories I most enjoy telling has to do with a kind of douchebag apprentice brough back from the brink. Early in the Ballroom’s history, a confident, beloved young woman approached Sarah and me to make a complaint. A young man her age had, she said, been engaging in some harmless flirting with her and a group of friends, when, through ineptitude or malice, he had raised the stakes with an overtly sexual proposition. Whether or not this was offered in earnest was impossible to determine, but we were given to understand that the conversation took a gross and inappropriate turn. He had been handily chastened by the young woman, but she thought we should know.

“Is this a kick him out situation or a talk to him and keep an eye on him situation?” I asked.

After a moment’s consideration, the estimable young woman replied, “I think it’s a talk to him and keep an eye on him kind of thing.” Sarah and I played rock paper scissors to determine which of us would deal with the goon, and it fell to me. I surveyed the miscreant from a discrete vantage. He was wearing a choker, but carried himself with a haughty fake confidence that read: Bro. Something confusing and unfortunate was happening, an unintentional genre mixing. I made my approach.

“Hi, I’m Michael. It seems like you have gone and made a whole bunch of people uncomfortable. What are we going to do about this?” We find it best to come out hard and leave these folks on their back foot.

“Yeah, I screwed up. I apologized, but it was kind of uncomfortable. I should apologize again.” Interesting. I sensed unexpected sincerity rising up from within the circle of his choker.

“Would you like to understand what you did wrong?”

“Sure.”

“You raised the stakes; you went from zero to 60. That kind of thing is best left in the hands of people, other people, who have the awareness to tell whether or not someone is inviting a more intense interaction.”

“That makes sense.”

“You are now forbidden from escalating situations. It’s fine to flirt with people, but since it’s going to be amateur hour for a bit, it’s your job to let them drive, and, with each response, come in right under wherever they left it. Follow them up the ladder of intensity. When they stop, you stop.” I illustrated this with my hands held out, palms down, moving each above the other. Maybe he was a visual learner.

The young man looked at me as if I’d invented fire, and he seemed to be genuinely relieved at the prospect of interacting with women and keeping his whiskers unsinged. There was no evil here, just dangerous stupidity. Sarah and I checked in from time to time, but we never had trouble with him again. He stopped wearing the choker, which was a relief to everyone.

***

We’ve had any number of such small scale successes, which we consider part of our job, since subculture communities really do function as finishing schools for the socially awkward. Some of the failures, the people we’ve tried to work with and ended up kicking out, however, have been immensely painful. Some of them were friends, some of them highly successful, promising people whose vanity or insecurity made them weasels. I don’t think that the human capacity to start well and end badly through exhaustion or bad company or poisonous ideas has been sufficiently discussed, and we have tried to maintain compassion even in the worst circumstances, despite the tendency among our fellow lefties to mistake hatred for ideological commitment. It is hard to keep someone’s humanity in mind while you move staunchly against them (and they don’t tend to recognize or appreciate the effort), but I’m not sure what else to do.

Over time, being on the lookout for bad behavior has become habitual, and we have struggled to keep the attitude from spreading out into daily life like an invasive plant. I know that both Sarah and I have had long stretches in which we walk down the street and look at the people passing, thinking: creeper, diddler, idiot. The national dance community seems to combat this by balancing cynicism with effusive hero worship of a rotating cast of types—black women, trans people, women who lead, men who follow, and on and on—people who, however deserving of recognition and power, can never rise to the level of responsibility the community is so eager to foist on them. The intensity of the hero worship is equaled only by the intensity of the hateful glee that surfaces when any of these paragons shows a scintilla of human frailty. We’ve seen too many people praised whom we know to be villains or merely average-grade shitheads or self-serving weasels to go in for this kind of approach. We also know that, like everybody else, our worst moments wouldn’t bear much scrutiny. All of this is to say that, without a counterweight to the sense that we are always on watch for some kind of wickedness—without hero worship to provide meaning and direct ambition—it has been difficult for us, at times, not to despair.

In this frame of mind, I like to lurk next to the sound booth at the back of the ballroom and take in the whole thing, the unbelievable sight of people dancing, laughing, hugging. In those moments there seems to be a sufficiency of goodness in how people can gather for an innocent purpose, how they plant themselves in a seemingly random place, form relationships, and start conjuring meaning as fast as they can. This beautiful tendency is entirely unmitigated save by the corresponding truth that one act of bad faith or selfishness, one damaged person with even prosaically bad motives, can do incalculable harm. The great mystery of daily life and community—and the reason for all the bravery that people exercise with such regularity that it goes unnoticed—is that the work of a year, a decade, or a century can be undone in a moment.

I struggle with that every day, as I think most adults do after a certain age. I have spent 10 years in this room, working and failing and trying to savor the occasional triumph. I’ve had the honor of watching people grow up, get married (often in the ballroom), and have children. I have seen acts of contempt and self-indulgence, acts of corruption. I have watched people become the best and worst versions of themselves, and I have darkly meditated on how little I had to offer one way or the other.

***

So much of community has nothing to do with change or progress, I think, and I always smell marketing dreck when people talk that way (including when I talk that way). It is more accurate to describe communities at their best as providing solace, as venues where one’s confusing existence can be witnessed, which is no small thing. Life is coming to get all of us, and it is best to face that fact in company. Some of you may remember that a good man died in this room some years back. I won’t insult the bereaved by talking about what that long night meant to me or how it felt for the entire staff, but I can say that I was tremendously proud of the grace and dignity displayed by everyone in attendance that night, from regulars to first-timers to the band. There was nothing anyone could do—although those who were qualified tried—but the quiet care and love in the place were palpable. If it had been me on that floor, I would have considered myself well served. The awful fact of the thing remained, but its context made it human.

***

Looking back over this, I see that I have hardly mentioned dancing at all, which makes a certain sense since both Sarah and I have been outliers who have always seen organizing dance shit as a way of getting at something else entirely. I have been dancing since the previous century—and I traveled and competed and even taught a little—but from very early on I understood and was struck by the power that social dancing has to create community, and that has always been what this is about for me, despite my prickliness and hostile disposition. It has been no accident that I, a pastor’s kid, ended up presiding over weekly gatherings in this church. As I said, there seems to me to be something holy that happens whenever people gather for an innocent purpose. I often laugh to think that, out of my cohort of college friends, I should be the only one who took a path entirely outside of teaching and the academy. They have gone on to lead successful and deeply decent lives, and I am still lurking in these odd shadows. I have found meaning in this small work. I am proud of my friends and content with what I have done. An enviable position, overall.

A word on my hostile disposition. The other day I did some back of the envelope math, and was amused to realize that—despite how little all of this has had to do with dancing for me—I have taught a staggering number of dance classes since this place began, and I have been dancing around at our events for thousands of hours more. I have generally worked the room and asked people to dance and said yes when they have asked me. This makes it indisputable fact that, despite everything about me, I have spent the bulk of my professional life not just interacting with people but literally holding them in my arms. Thousands of them. This is both wildly implausible and absolutely true.

When Sarah wants to make fun of me, she reminds me that I am, technically, a dancer.

***

This is not what I will be doing for the rest of my life, and from most angles it does seem like a frivolous pursuit taking place in what the uninformed would consider a backwater. We have, however, maintained our independence, operating as we see fit and preserving generous scope to fight the battles we thought worth fighting. Even in a narrow field you can learn a lot by removing the bumpers. There was no boss or board for us to blame for our failures or whose policy we were required to enforce. We simply made up the rules as we went along, trying to act in good faith. This is incredibly dangerous and prone to abuse, of course, and we have often failed. Still, when bad actors or real estate speculators or downright weasels have crossed our path, we had the independence to fight back as hard as we could, and I count it among the treasures of my life that we sent quite a few yelping back out of the circle of our influence. In the bad old days, when our original, wicked business partner betrayed the community’s trust and put the place at risk, Sarah and I did everything we could to put things to rights. Sarah, in fact, did more than anyone would have the right to ask.

What it has meant to me to work with the best of friends and business partners all of these years goes far beyond anything I can express here. I will only say that more than half of what is best in this place is due to her. At the beginning of the pandemic, when I asked her if we should take out a gigantic personal loan to keep the place afloat, she was game, as I knew she would be. As she always has been. They don’t make people any better or more daring.

***

This community has never let us down. Not once. It raised money for us at the beginning of the pandemic, then again for artists (The Mobtown Telethon!), and then again for the Georgia senate runoffs (Baltimore Saves America!). No call for help or volunteers has ever gone unanswered since we all got together ten years ago and built the floor, plank by plank. Members have testified in court on their friends’ behalf, comforted one another in grief, funded pet surgeries, taken one another in, and danced their hearts out. We have tried to measure up to that kind of staunch consistency, and I believe I can say that we never disgraced ourselves. We tried hard to do right by the community, and we have worked with a great number of people trying to do the same, which was an honor. I do not know what will come of all of this as we move forward, but I do know that I believe as strongly now as I did in my younger, scrappier days that if you put a bunch of people in a room together and tell them that magic can happen, they will make it for themselves. That is one of the oldest truths available, and I have spent most of my life leaning on it. What a way to make a living. Thanks, everybody.